Growing Knowledge to Protect Pollinators

go.ncsu.edu/readext?983562

en Español / em Português

El inglés es el idioma de control de esta página. En la medida en que haya algún conflicto entre la traducción al inglés y la traducción, el inglés prevalece.

Al hacer clic en el enlace de traducción se activa un servicio de traducción gratuito para convertir la página al español. Al igual que con cualquier traducción por Internet, la conversión no es sensible al contexto y puede que no traduzca el texto en su significado original. NC State Extension no garantiza la exactitud del texto traducido. Por favor, tenga en cuenta que algunas aplicaciones y/o servicios pueden no funcionar como se espera cuando se traducen.

Português

Inglês é o idioma de controle desta página. Na medida que haja algum conflito entre o texto original em Inglês e a tradução, o Inglês prevalece.

Ao clicar no link de tradução, um serviço gratuito de tradução será ativado para converter a página para o Português. Como em qualquer tradução pela internet, a conversão não é sensivel ao contexto e pode não ocorrer a tradução para o significado orginal. O serviço de Extensão da Carolina do Norte (NC State Extension) não garante a exatidão do texto traduzido. Por favor, observe que algumas funções ou serviços podem não funcionar como esperado após a tradução.

English

English is the controlling language of this page. To the extent there is any conflict between the English text and the translation, English controls.

Clicking on the translation link activates a free translation service to convert the page to Spanish. As with any Internet translation, the conversion is not context-sensitive and may not translate the text to its original meaning. NC State Extension does not guarantee the accuracy of the translated text. Please note that some applications and/or services may not function as expected when translated.

Collapse ▲

Ceratina bees are one of the pollinators found nesting in old stems.

As awareness of the perils facing pollinators continues to rise, many people want to know what they can do in their home landscapes to protect them. In addition to planting pollinator-friendly plants that provide nectar and pollen resources, how you manage plants can increase or decrease their value to pollinators. This includes practices such as not spraying flowering plants with pesticides and how and when you trim perennial stems.

In North Carolina, over a dozen species of bees and beneficial solitary wasps build nests and lay their eggs inside hollow stems, including the old flowering stems of herbaceous perennials. Current information about when to cut back stems at the end of the growing season is unclear and, at times, contradictory. This raises the question, “How should we manage perennial stems to increase the ability of residential landscapes to provide habitat for pollinators?” To answer this question, NC State experts Elsa Youngsteadt and Hannah Levenson designed a research project and worked with Extension professionals and NC State Extension Master Gardener℠ volunteers across the state to gather data.

Trimming perennial stems to leave a few feet standing above ground level provides habitat for stem-nesting pollinators.

The project involved Extension Master Gardener volunteers changing the way they manage herbaceous perennials in the landscape. In the first year of the project, instead of cutting perennial stems all the way back in the fall, they trimmed them to leave 18 inches standing above ground level. The following year, volunteers collected over 2,000 of the previous season’s stems and sent them to Elsa and Hannah at NC State to determine if any pollinators were using them as nesting habitat. Samples of old stems were collected in late winter, spring, summer, and early fall.

More than half of the samples Master Gardener volunteers collected in the spring and summer contained pollinators or beneficial insects. Occupants included three species of Ceratina bees (also known as small carpenter bees), leafcutter bees, potter and mason wasps, and grass-carrying wasps.

Stem nesting bees build cells inside hollow stems where they lay their eggs. Immature bees, known as larvae, grow inside the stems, feeding on pollen left by the mother bee. The Ceratina bee larvae seen here were found in the old stems of rough goldenrod (Solidago rugosa). Image taken spring 2023, by Irish Youmans.

Based on these findings, Elsa and Hannah share the following recommendations to maximize pollinator habitat in your landscape:

- Trim perennial stems back in fall or winter to leave 1-2 feet standing above ground. While these stems will not be occupied the first winter, they will be available for pollinators and beneficial insects to use as nesting sites the following spring and summer.

- Waiting until late winter to trim stems will give birds and wildlife time to feed on seed heads, increasing the number of species supported.

- Once trimmed, the stems require no further maintenance and will naturally disintegrate in future seasons.

Elsa and Hannah note that stems that have not been trimmed at all can still be used for nesting habitat, but cutting the stem ends may make them more accessible to nesting bees and gives the garden a tidier appearance. On the other hand, cutting stems off at ground level removes them from the ecosystem altogether and prevents them from ever becoming a nesting resource.

Old stems containing nesting pollinators and solitary wasps were collected from a range of popular perennials that also provide valuable nectar and pollen resources, including the following species native to the southeast:

- Swamp milkweed, Asclepias incarnata

- Purple coneflower, Echinacea purpurea

- White snakeroot, Eupatorium rugosum

- Joe Pye weed, Eutrochium species

- Bee balm, Monarda didyma

- Wild bergamot, Monarda fistulosa

- Mountain mint, Pycnanthemum species

- Green-head coneflower, Rudbeckia laciniata

- Fireworks goldenrod, Solidago rugosa ‘Fireworks’

- Fanny’s aster, Symphyotrichum oblongifolium ‘Fannys’

Many native perennials, such as this purple coneflower, offer both food and nesting resources for pollinators. Image by Charlotte Glen, NC State.

Adding these flowering perennials to your landscape and following the recommendations on trimming will maximize the benefits your landscape offers pollinators and help ensure that these important species thrive.

Many thanks to the Extension agents and Master Gardener volunteers based in Chatham, Chowan, Forsyth, Perquimans, Cumberland, Forsyth, Haywood, Lee, Vance, and Wilson counties who were involved in this project! Their efforts have grown our knowledge of sustainable gardening practices that North Carolinians can apply in yards and landscapes across the state to protect and conserve pollinators.

This project was possible thanks to funding provided by NC State Extension administration through the Horticulture Working Groups. We extend a special thanks to Leslie Rose, Extension horticulture agent in Forsyth County, for coordinating agent and volunteer participation in this project.

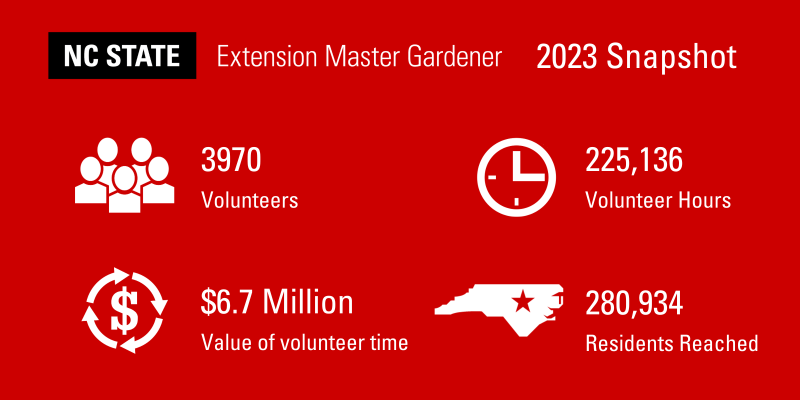

The NC State Extension Master Gardener℠ program is a statewide network of volunteers and Extension educators working in N.C. Cooperative Extension county centers and on NC State campus. Through education and outreach, we connect people with the benefits of gardening and empower North Carolinians to cultivate healthy plants, landscapes, ecosystems, and communities.

Explore stories from our 2023 Annual Report, which celebrates our work to help North Carolinians improve their lives and grow our state.

Join, support, or connect with Extension Master Gardener volunteers in your community.